Memorial

History of the Ravensbrück Memorial (1959-2020) –Overview

The efforts to create a worthy Memorial in Ravensbrück already started in the first years after the liberation of the Camp. In July 1948, a "Crematorium Committee" visited the site of the former Women's Concentration Camp, which was then already used by the Soviet Army.

The Committee consisted, among others, of Emmy Handke for the "Ravensbrück Committee" of former prisoners as well as representatives of the UN and the local administration.

The minutes of the visit stated that the site was in a "disgraceful condition" and had to be "prepared" for an international commemoration ceremony scheduled for 12 September of the same year.

Immediately after the liberation, prisoners who had died shortly before or after liberation were buried in several cemeteries near the Concentration Camp. In the early 1950s, a burial area was built at the outer camp wall.

By a decree of the Central Committee (CC) of the SED in 1952 on the establishment of the memorials in Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück, the commemoration of the historical sites of the concentration camps was officially raised to the status of a state affair of the GDR, which was founded in 1949. Subsequently, in May 1954, the Buchenwald Memorial's collective of architects was commissioned also with the overall design of the memorial site in Ravensbrück.

Survivors of the camp also actively contributed to the creation of the memorial site. One of the central protagonists was Erika Buchmann, who developed a considerable and far-reaching activity, supported by her numerous amicable and political contacts. This was reflected in the extensive communication with other survivors, camp communities and government agencies. In February 1958, for example, in a letter to Katharina Jacob from Hamburg, she asked for memories of "the struggle and camp life of the Ravensbrück people" to be included in the "design of the museum" and "a book [...] about Ravensbrück". The "Ravensbrück National Memorial Site" was finally opened on 12 September 1959 as one of the three Concentration Camp Memorial Sites in the GDR. It comprised a part of the former concentration camp grounds and its buildings, including the Crematorium and the Camp Prison.

According to official information, about 50,000 people moved from Fürstenberg to Ravensbrück on 12 September 1959, after a wreath-laying ceremony had previously taken place at the Soviet memorial in Fürstenberg. The central ceremony was held on the newly created Memorial Site on the banks of Lake Schwerdtsee, where 265 invited guests were seated on a tribune. After the welcoming words, presented by Aenne Saefkow's daughter Bärbel, Rosa Thälmann held the inauguration speech, followed by speeches from representatives of 19 national delegations.

Since 1959, the Camp Museum in the former Camp Prison wasintegral part of the memorial site. Survivors from many European countries donated objects, documents, artwork and drawings from the time of their imprisonment.

In the early 1980s, representatives of the different countries set up exhibitions on their persecution and imprisonment history in the rooms of the former camp prison. From 1984 the former commandants‘ headquarter of the camp housed the main exhibition of the Memorial, entitled "Museum of the Anti-Fascist Resistance Struggle". The Soviet Army and its successors used most of the former camp grounds until 1994.

After the reunification of the FRG and GDR, the Memorial became part of the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation in 1993. During the reorganisation/redesign in the early1990s, the previous main exhibition was replaced by two new exhibitions. Since 2013, the former commandants‘ headquarter again houses a new main exhibition. One of the former female guards' houses and one of the "Führerhäuser" of the SS personnel are also open to the public. In September 2019 the Ravensbrück Memorial celebrated the 60th anniversary of its existence.

The Spanish Room of Remembrance

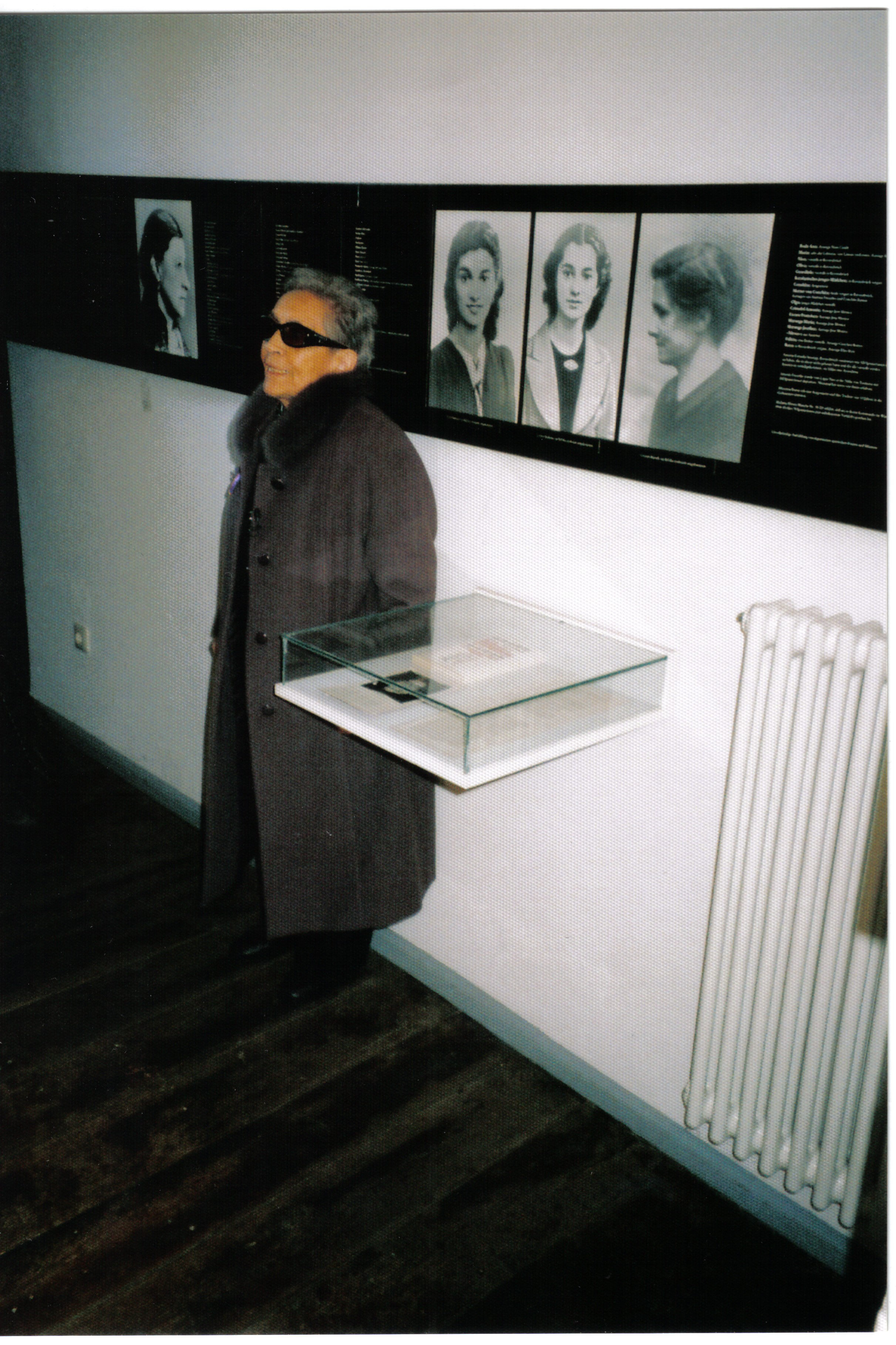

Inaugurated in the former bunker on the grounds of the Ravensbrück Memorial in the spring of 1989, the room is part of the legacy of the more than 100 Spanish women detained in Ravensbrück.

Neus Català i Pallejà, renowned fighter for the memory of all Spanish women prisoners, had taken the initiative. The survivors themselves designed the room at the centre of which is the flag of the Second Republic (1931-1939) for which the Spanish detainees had fought.

On display in a showcase is the book by Neus Català i Pallejà, "De la resistència i la deportació. 50 testimonios de mujeres españolas", published in Barcelona in 1984 and reedited there in 2000 and 2015. It came out in France in 1994 under the title "Ces Femmes Espagnoles de la Résistance a la déportation. Témoignages vivants de Barcelone à Ravensbruck", and in Germany, also in 1994, under the title "In Ravensbrück ging meine Jugend zu Ende".

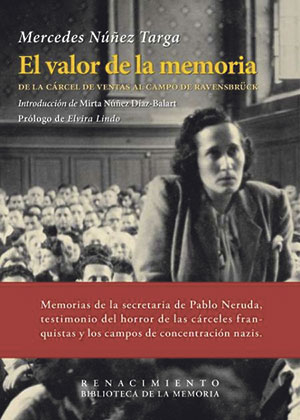

Other books in the showcase are the works by Mercedes Núñez Targa, "Cárcel de Ventas", published in Paris in 1967, and "El carretó dels gossos", published in Barcelona in 1980. In 2016, the publishing house Renacimiento issued "El valor de la memoria", an anthology of those two books.

The photos taken during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) illustrate the enthusiasm and determination with which the people defended the Second Republic under the battle cry NO PASARAN! - "They shall not pass!" But they also recall the suffering and destruction that Franco’s coup had brought to the Spanish people.

The photos highlight as well the prominent role of Dolores Ibárruri (1895-1989), "La Pasionaria", in the defence of the Second Spanish Republic against Franco.

The painting in the front section of the room is by Angel Hernández, defender of the Second Spanish Republic and former prisoner of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp.

Titelbild Buch Mercedes Nunez Targa

Titelbild Buch Mercedes Nunez Targa

The Italian Memorial Room

The cell in memory of the Italian deportees was designed by the architect Ludovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso who used the walls of the small space of the cell by inserting the designs of Violette Lecoq, French deported to Ravensbrück, of the same Belgiojoso deported to Mauthausen, and other survivors from different lagers.

On the short wall of the cell there is a large outline of Italy with the areas of origin of the deportees indicated and a book with their names, based on research carried out up to the eighties.

We believe, as ANED National Association Italian Deportees, that the cell in memory of the Italian deportees must be rethought with a contemporary footprint of greater impact for the new generations.

Ambra Laurenzi

Salle commémorative française

Memorial Space Poland

Polish women sent to KL Ravensbrück, were of different social and educational background as well as age. In the place where suffering and death were an every day reality, they set up “Mury” ( Walls) scouts self-help group, and organized secret teaching where elder prisoners shared their knowledge with the younger ones. They also became involved in resistance activities and addressed special attention to “ rabbits”- the prisoners used for pseudo-medical experiments, frequently managing to save them from execution.

The camp solidarity and life-long friendships originated there, nurtured the rapid growth in the number of Ravensbrück Clubs, which started in Poland as early as in the autumn of 1945. These made up a network that allowed them to effectively support one another. However, the priority for the Polish survivors was to preserve the memory of their own experience and of their murdered fellow prisoners. Thus they documented the crimes of the German oppressors in many publications such as: "Zwyciężyły wartości” (The Values Won) by Urszula Wińska (1985 r.), "Ravensbrück" by dr Wanda Kiedrzyńska (1961 r.), "I boję się snów" ( And I Fear Dreams) by dr Wanda Połtawska, and in the collective work from 1968 “Ponad ludzką miarę. Wspomnienia operowanych w Ravensbrück" ( Beyond Human Means. Memories of the Operated on in Ravensbrück). The survivors wanted to share the testimony to their values and experience with future generations.

The Polish survivors wanted no further reoccurrence of the Ravensbrück horror, of the suffering or death due to one’s nationality, religion or race. It was them, the former prisoners, who in the post-war times, so complicated politically and meagre economically, in unison and with great dedication raised funds to arrange the memorial space commemorating their inmates, mothers, grandmothers, sisters and other dear ones. All donations to the Polish memorial space are registered in the archives of the Polish Ravensbrück Club. One of the entries showing the attitude of the donors states that two survivors, the sculptors Zofia Pociłowska- Kann and Wacława Bielecka renounced their fee, and most work was done in a DIY manner.*

The most important elements of the Polish memorial space are the life- size photographs showing the results of the pseudo- medical experiments: misshaped, mutilated legs of the Polish women, the data concerning 74 women used for experiments, precise numbers of the Polish prisoners, and the quotations from the testimony given by the survivors in the Nuremberg trial. A great role among the exhibits in the Polish memorial space plays, both as testimony and a piece of art, the sculpture created by already mentioned Zofia Pociłowska-Kann, a former prisoner and world-famous artist.

The survivors, for whom the Polish memorial space is of great historical and deeply personal value, explicitly call for continuing its original format and idea as testimony to Ravensbrück, life in Poland during World War II, and to the post-war reality. It is of great importance to pass it on to the future generations of Europe: only through unbiased awareness and understanding of the key historical events once shared by different European nations is it possible to create true solidarity of united Europe.

Distance in time naturally makes the importance of events and emotions relative; the contemporary, focused on their current problems, look at the past through the present filters, thus losing the right comprehension of the historical reality, often treated as unnecessary burden. For that reason, the more distant the experience of the Ravensbrück survivors , the stronger the call for authentic testimony that contemporary and future generations might refer to. Aware of the expectations of the younger visitors and new museology trends, the Polish survivors suggest that new technologies should be used in the arrangement of the Polish memorial space, yet preserving its original purpose and content.

Hanna Nowakowska, vice president, January 2021

- “Information Regarding Making the Exhibition in the Museum Cell on the Premises of the Former Ravensbrück Death Camp, 1991.”

Innenansicht des polnischen Gedenkraumes (1)

Innenansicht des polnischen Gedenkraumes (2)

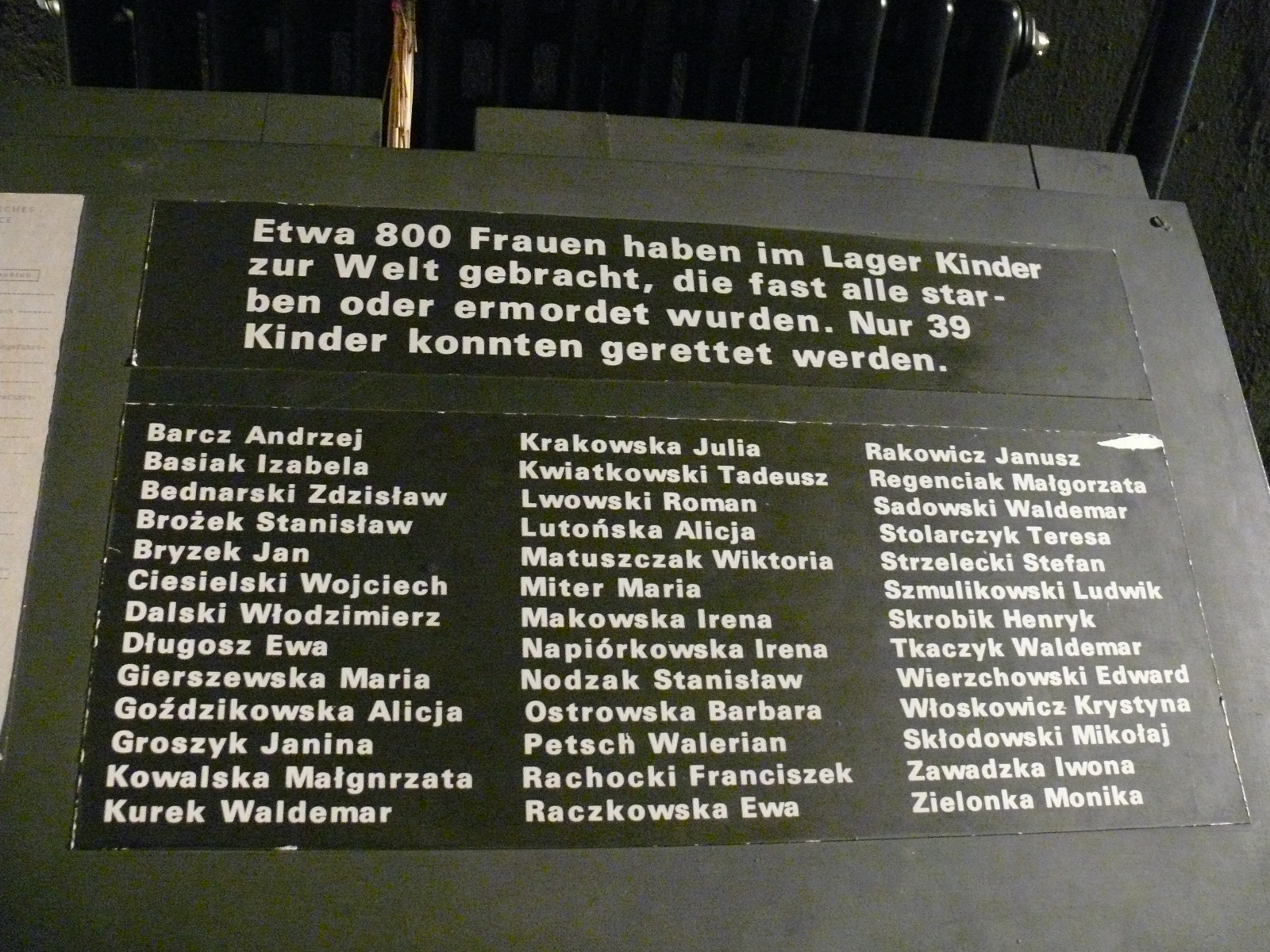

Polnischer Gedenkraum: Namen der überlebenden polnischen Kinder

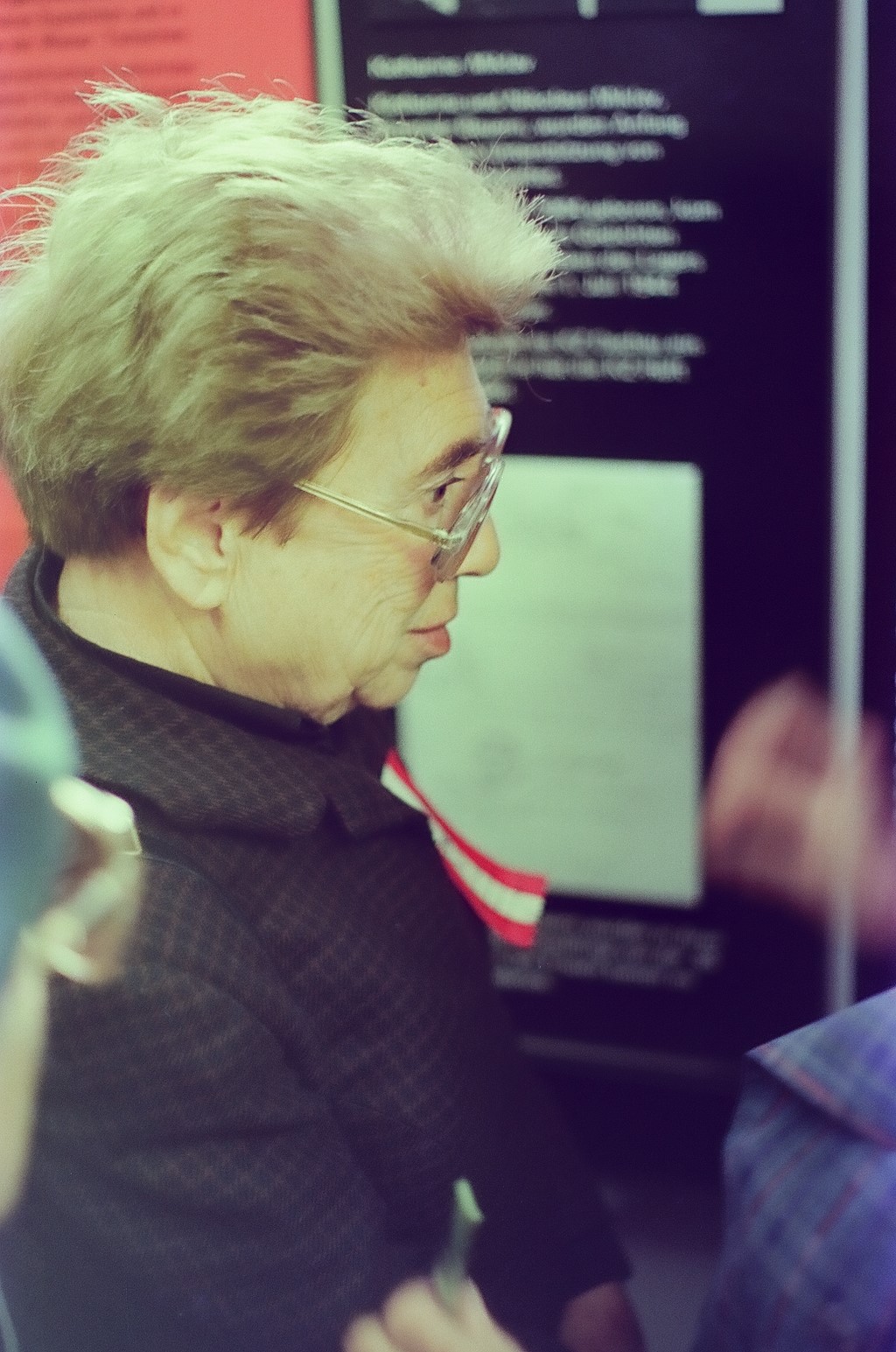

Janucz Rakowicz 2005 im polnischen Gedenkraum der MGR

Memorial space Austria

In preparation of the opening ceremony of the Ravensbrück Memorial site in 1959 all camp communities had been invited to write down witness reports of their time in the concentration camp and to contribute some personal belongings from those days to a museum. Moreover, each national group of prisoners had been offered to arrange a cell in the former bunker according to their individual preferences.

Bertl Lauscher and Toni Bruha reported to their fellow members about the former prisoners’ meeting that had taken place in Berlin on November 17 and 18, 1956. The two had been chosen to represent the Austrian Camp Community Ravensbrück (ÖLGR) in the International Ravensbrück Committee. They informed that the museum was to be installed in the former bunker. The ÖLGR newsletter of July 1957 wrote: “We formed a committee for the museum, that is to say for the decoration of our cell in the museum. This committee has the purpose to collect any such material that can be found in Austria: witness reports from the camp, pictures of the deceased and the executed as well as their biographies, poems, images, songs, drawings, and sculptures – in short, things that were created inside the camp. Furthermore, pieces of memory such as clothes and laundry from the camp, numbers, triangles, shoes, mules, dinnerware, keepsakes of all kind. We also ask the fellow members to let us know the names of artists interested in cooperating with the committee.”

Hilde Zimmermann was named the contact person for all matters regarding the exhibition. Other committee members were Toni Bruha, Hanna Sturm, Bertl Lauscher and Valerie Tartar. The structure of contents and the selection of items, pictures and texts would keep the ÖLGR’s women very busy for the following two years. Together with the architect Margarete (Grete) Schütte-Lihotzky a concept for the design of the museum was developed hoping that “a dignified memorial will be established in the place assigned to us in the bunker.” ²

For the installation of this Austrian memorial the ÖLGR had two cells in the former bunker at its disposition. The first was used to illustrate “Nazi activities in Austria before 1938“, as well as the German invasion of Austria. A map of Austria showed regions of the resistance’s activities. The role of women in the fight against fascism and war was particularly highlighted; here the story of two resistance fighters from Styria, Mathilde Auferbauer and Johanna Rainer, served as an example. The second cell was dedicated to the Austrians who died at Ravensbrück and included the biographies of ten murdered women. The exhibition also depicted the concentration camp’s structure and functions, presented important numbers and facts from the Nazi and war years and culminated in the women’s wish for peace. Grete Schütte-Lihotzky and Hilde Zimmermann personally curated the correct presentation of all exhibits and text boards.

In order to inform a large number of Austrians of the atrocities that had taken place at the camp a copy of the exhibition would be shown successfully throughout Austria for many years to come. Based on their experience the women had made as guides through the exhibition the ÖLGR published a brochure in 1963 titled: “What do I care about that?”

In the presence of delegations of former prisoners and their families from many countries the National Memorial Ravensbrück was inaugurated on September 12, 1959. During the following years the various exhibitions that had been created by the camp survivors in the former bunker became an important point of reference for the visitors of the memorial site, among them many youths. They showed not only the horror and the suffering inside the concentration camp. They also informed about the prisoners’ attempts to treat each other with solidarity despite the extreme conditions and to oppose the hellish fascist regime with their humanity, their dignity, their resistance and their will to survive.

In 1985 the former bunker was flooded and parts of the exhibition were destroyed. Many of the Austrian exhibits were lost forever. Some ÖLGR members were able to retrieve only very few pieces from the mud. The creation of a new exhibition was inevitable. Austrian survivors were asked anew to support the restoration of the exhibition spaces with memorabilia.

Hilde Zimmermann was significantly involved again in the preparations of the exhibition. It was decided to largely maintain the concept of the exhibition’s first edition while adding some new content such as the Christmas party of December 1944 which had been organized for the camp’s children as a sign of cohesion and solidarity. This time the architect Prof. Ernst Fuhrherr supported the project with his graphic design.

On September 19, 1986 – only one and a half years after the tragic flood – the ÖLGR was able to unveil its newly designed memorial spaces to a big delegation from Austria led by the ÖLGR’s chairwoman Rosa Jochmann. ³

Rainer Mayerhofer, who reported for Austrian journal Arbeiter-Zeitung, described the exhibition as “impressive documentation which shows the rise of fascism in Austria from the homemade beginnings up to the cruel Nazi regime.” He also shot some pictures of the event.

The Austrian Camp Community and Friends (ÖLGR/F) assumes the National Memorial Ravensbrück will see to it also in the future that the Austrian memorial spaces will remain available to new generations of visitors: authentic, unmodified and exactly as the surviving women had conceived and arranged them.

On the occasion of a workshop at Ravensbrück in late October 2019 on how to deal with the national memorial spaces in the future the ÖLGR/F’s representative Vera Modjaver, stated: “…We agree that significant historical changes have taken place. However, we want to preserve the exhibition spaces in the currently present design. To us they are a legacy, not least of the last surviving comrades. I call them comrades because this is how they call themselves. The rooms of the exhibition as they are today give insight into the political events of that time and into how it was possible that such inhuman and degrading places could come into being. ... As a form of compromise, we could imagine the creation of new memorial spaces in other forms, but the cells in the bunker should remain as they are... “

*1. Mitteilungsblatt der ÖLGR vom Juli 1957 2. ibid.

3. Helga Amesberger, Kerstin Lercher; „Lebendiges Gedächtnis. Die Geschichte der österreichischen Lagergemeinschaft Ravensbrück“, mandelbaum Verlag 2008, ISBN 978-3-85476-254-6

Dr. Broda und Dr. Litschke eröffnen die Ausstellung, Foto: Rainer Mayerhofer

Hermine Jursa bei der Eröffnung der Ausstellung; Foto: Rainer Mayerhofer

Lotte Brainin bei der Eröffnung der Ausstellung, Foto: Rainer Mayerhofer

Rosa Jochmann bei der Eröffnung der Ausstellung, Foto: Rainer Mayerhofer

Toni Bruha bei der Eröffnung der Ausstellung, Foto: Rainer Mayerhofer

Toni Lehr bei der Eröffnung der Ausstellung, Foto: Rainer Mayerhofer