Solidarity and Resistance

In the Concentration Camp women were to be deprived of their identity and dignity. They were just supposed to be just numbers. Any rebellion against the SS and their system of humiliation, disdain for humanity and extermination was punished. Every human emotion for each other was suppressed.

Yet there was humanity among each other, women stood up for each other, and were there to support each other. Sometimes there was only a smile or an encouraging word, a song sung together or a small gift.

Women who had been sent to the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp for political reasons, who had already been organized before and who had offered resistance against the inhuman Nazi regime, found themselves in the camp anew, supporting each other wherever possible, even under the cruel living conditions. This is proven by countless examples in the descriptions of the survivors after 1945.

And there were also organized actions, to whose success often several women of different nations were contributing. The foundation for this was the trust and camaraderie between women of different nations and the good contacts between the small illegal resistance groups of different nations in the blocks.

The friendships from that time within the international camp community continued after the war with the founding of the International Ravensbrück Committee by the survivors. One of the first German-language summaries of the cohesion, solidarity and resistance in Ravensbrück appeared in 1959 in the book "Die Frauen von Ravensbrück". It was written under the direction of Erika Buchmann (1902-1971), who was herself a prisoner in Ravensbrück and could report from her own experience. The following forms are mentioned here:

Joint action as a means of self-defence, formation of national resistance groups in the blocks, obtaining and jointly evaluating news from newspapers and other sources, political training, organising small cultural events, producing and giving away small works of art, celebrating birthdays and national days of remembrance, church services and other religious celebrations, writing fake letters to give comfort and joy.

(Source: "Die Frauen von Ravensbrück", p. 120-133, Komitee der Antifaschistischen Widerstandskämpfer der DDR (ed.), compiled and edited by Erika Buchmann, 1959, Kongress-Verlag Berlin)

The historian Dr. Wanda Kiedrzynska (1901-1985), who was also a former prisoner of the Ravensbrück concentration camp, dedicated an entire chapter of her book "Frauenkonzentrationslager Ravensbrück" ("Ravensbrück - kobiecy obóz koncentracyjny") to solidarity and resistance in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. It was also she who, during the meeting of the International Ravensbrück Committee (IRK) in May 1971 in Jaszowiec, systematically worked out the different manifestations of resistance in the concentration camp for the first time in her presentation:

Mutual help among equals, cohesion and support in scout groups ("Mury" - "Walls"), connections with the outside world, culture and educational work in any form, readings and discussions of newspapers and news, religious life, secret teaching and learning, artistic and performing activities, political life.

The results of the May 1971 meeting were recorded in a protocol "Resistance in Ravensbrück".

(Source: "Ruch oporu w FKL Ravensbrück, spotkanie Miedzynarodowe Jaszowiec- maj 1971 r.", Zwiazek Bojowników o Wolnosc i Demokracje Zarzad glowny, Srodowisko Ravensbruck, Katowice 1972)

In their memories of their imprisonment in the Ravensbrück concentration camp and its subcamps, many of the women also described the sabotage of production in the German factories, where they were forced to do forced and slave labour.

There were also examples of how female comrades were successfully rescued from the threat of punishment or execution.

In retrospect, women of various nations highlighted Christmas 1944 as a special event of solidarity with the weakest in the camp, the children. The weeks of preparation for the celebrations, the creation of many small gifts, the organisation of additional slices of bread and sometimes small snacks for the children also contributed to strengthening the cohesion and will to survive of the women involved.

The manifestations of solidarity and resistance of the women in Ravensbrück mentioned here are also described by Helga Amesberger and Brigitte Halbmayr, the evidence of which was gathered in countless interviews with former Austrian prisoners of the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

(Source: Helga Amesberger / Brigitte Halbmayr, "Vom Leben und Überleben - Wege nach Ravensbrück. Das Frauenkonzentrationslager in der Erinnerung", Documentation and Analysis, S. 179-193, 2001, Promedia Wien, ISBN 3-85371-175-89)

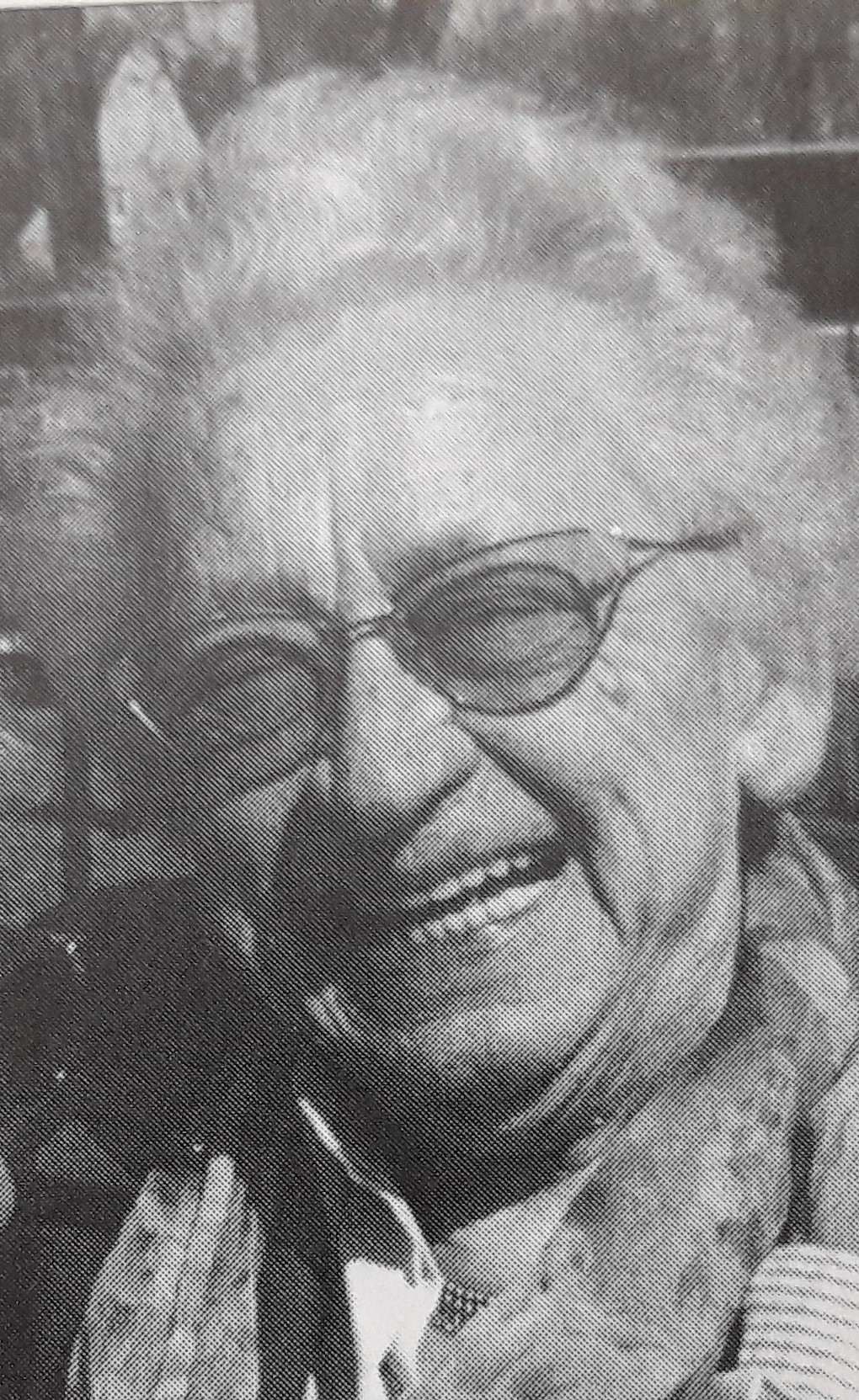

Paulette Lechevalier

Neus Català

Neus Català wrote:

"Although hunger twisted our stomachs, we were incapable of stealing even a crumb of bread from each other, but for the fight we were perfect thieves; sabotaging, sabotaging, sabotaging...

All our strength and worries were directed towards this.

However, it also meant deadly danger...When we saw what was demanded of us, we had to face the hardest question of conscience in our lives, but we decided to do it because we knew that even if we didn't do it, they would kill us in one way or another while others replaced us.

At the same time we saw a possibility to continue the resistance: not to produce and to sabotage the arming of the Nazis with all means."

(Neus Català, „In Ravensbrück ging meine Jugend zu Ende / In Ravensbrück my youth came to an end". Fourteen Spanish women report on their deportation to German concentration camps, edition tranvia Berlin, 1994, ISBN 3-925867-11-2)

Gertrud Müller

Gertrud Müller reports in her memoirs on the illegal camp committee:

"It was an international organization consisting of reliable women. ... The illegal camp committee ensured wherever possible that a certain amount of relief was provided for the prisoners. "

(Gertrud Müller, The first half of my life. Erinnerungen 1915-1950, p. 44/45, ed. Lagergemeinschaft Ravensbrück/Freundeskreis e.V., ISBN 3-00-014930-9)

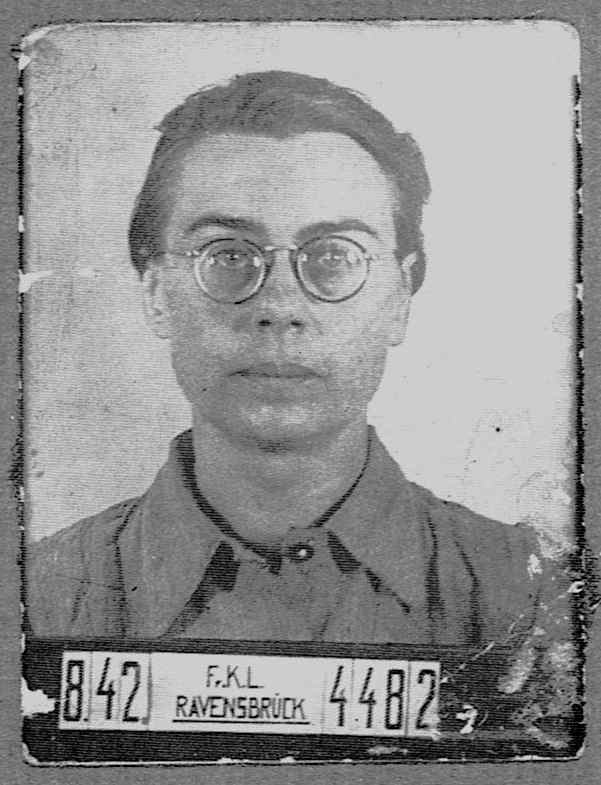

Melanie (Mela) Ernst (1893-1949)

The Austrian Melanie (Mela) Ernst had already gained experience in political resistance during the defence of the Spanish Republic from 1936 to 1939 and subsequently in the French Resistance.

Before she came to Ravensbrück in autumn 1943, she had already spent several years in prison. Together with Mara Günzburg, who had also taken part in the Spanish War against Franco, she initiated the networking of the individual national resistance groups, which acted largely independently of each other, to form an International Camp Committee in early 1944.

When Mara Günzburg was executed by the SS in Ravensbrück in October 1944, Mela Ernst took over the leadership of the international group.

At the end of 1944, the International Committee declared that each individual had to ensure that no one would be left under the wheels. The most important task was to make sure that no one let themselves go, ...further political training was carried out.

(Helga Amesberger / Brigitte Halbmayr (eds.), "Vom Leben und Überleben - Wege nach Ravensbrück. The women's concentration camp in memory” - Volume 2, Life Stories, Birgit Haller: Interview with Maria Berner, p. 20-26, 2001 Promedia, Vienna, ISBN 3-85371-176-6 and Volume 1, Documentation and Analysis, p. 199-200, Promedia, Vienna, ISBN 3-85371-175-8)

Ilse Hunger, Anna Hand and Mitzi Berner

The German Ilse Hunger and the Austrians Anna Hand and Mitzi Berner were employed in the "Arbeitseinsatz" office from 1943.

Together they were able to place prisoner women from different countries in certain work commandos. Marta Baranowska often sought contact with them when she wanted to help the Polish women in "her" block: that one or the other should not be sent on transport, that mother and daughter or siblings should not be separated, that easier work was needed for one or the other because of their poor health. She had always found understanding and help with Ilse.

Together with the prisoners of the "Revier" (the Camps sick-bay), the women of the "Arbeitseinsatz" office sometimes succeeded in saving human lives. Prior to the arrangement of transports to subcamps of the concentration camp, in some cases investigations of the prisoners were carried out in the "Revier". With false entries on the index cards by prisoners employed in the "Revier" confirming infectious diseases such as scabies or tuberculosis, it was possible to put some women back from hard labour.

On the other hand, transport to a subcamp could also be a chance of survival. One of those saved in this way was Marta Birek, a young Polish woman. When she was taken to Ravensbrück to be shot in the spring of 1945, Marta Baranowska passed on this news to the "Arbeitseinsatz-Büro. There Marta Birek was put on a transport list under a new name and number. She came out of the camp unrecognized and survived.

Erna Lugebiel later said about Ilse Hunger: "She was at this place the angel who did such work. She took names off the lists, exchanged prisoner numbers. Through these tricks many were saved, could live on with numbers of dead people."

Marta Baranowska (1903-2009)

Marta Baranowska took part in an action that succeeded in saving three Austrian women from being shot:

Toni Leer, Gerda Schindler and Edith Wexberg, Jewish women who had also been active in the communist resistance. They had come from Auschwitz to Ravensbrück in early 1945 and were to be executed here.

Mitzi Berner discussed with Marta Baranowska the possibility of hiding the three women in the Polish women's block. The prisoner numbers tattooed on their forearms from Auschwitz had to be surgically removed before new numbers could be assigned to them.

These operations were successfully performed by Dr. Maria Grabska (Poland) and Majda Mackovsek-Persjio (Yugoslavia).

Other women were involved in the rescue operation, including French women, as Neus Català recalled. With a Swedish Red Cross transport all three of them finally get to freedom.

("Ruch oporu w FKL Ravensbrück, spotkanie Miedzynarodowe Jaszowiec- maj 1971 r.", Zwiazek Bojowników o Wolnosc i Demokracje, p. 147)

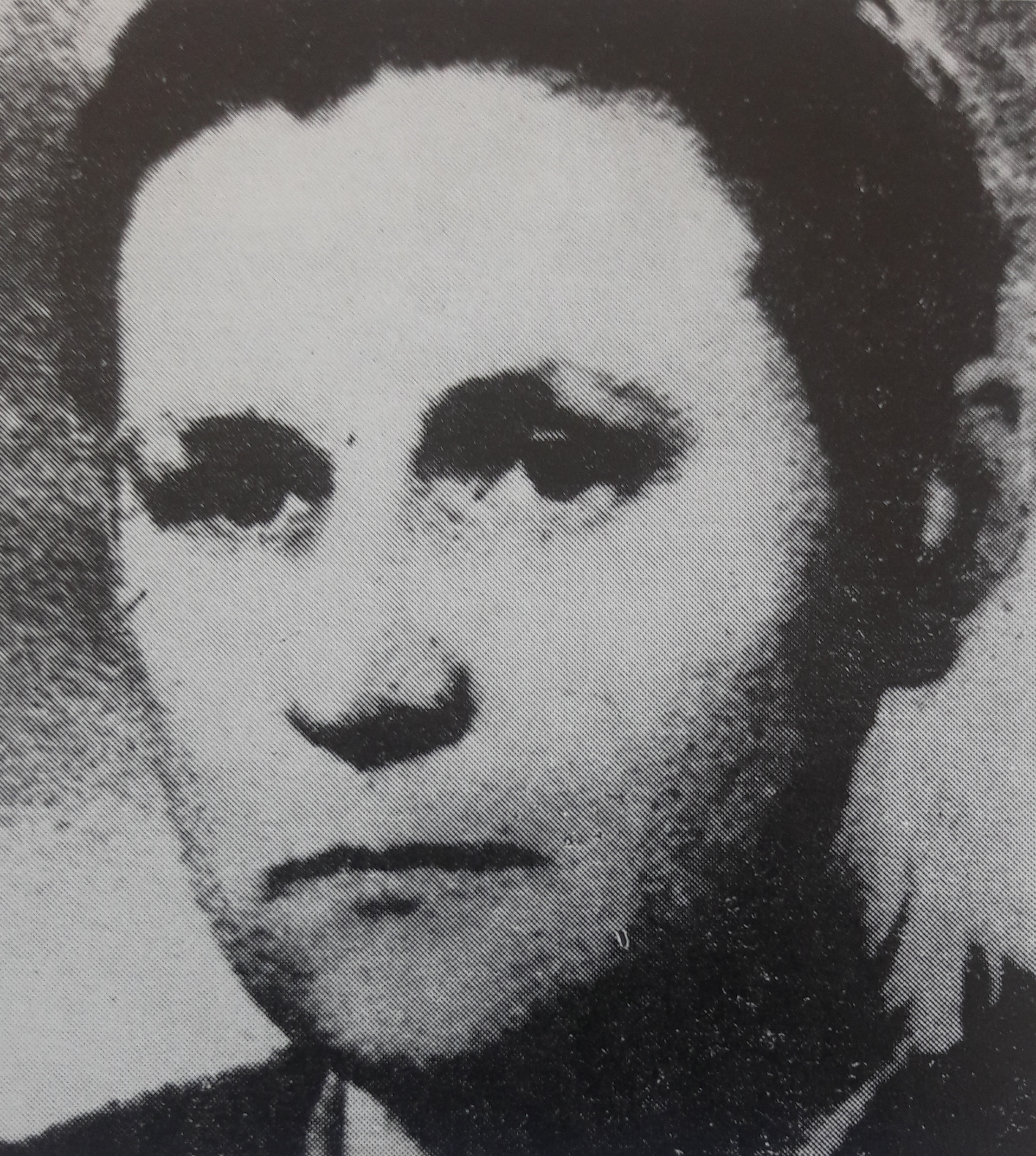

Martha Desrumeaux (1897-1982)

Martha Desrumeaux was an important pillar of the international solidarity network in Ravensbrück.

As a communist, leader in major strike struggles of French textile workers, leader of the workers of Lille in their struggle against the German occupiers, she was experienced in the resistance.

In Ravensbrück she organized the resistance groups of the French prisoners.

She worked in the bathroom and therefore had contact to every new arriving prisoner. She helped the weak, encouraged the despondent, passed on news, organized solidarity among the French prisoners and made connections with groups from other nations.

With Yvonne Useldinger (1921-2009, Luxembourg) she shared a sleeping place for a while and took on the role of a "camp mother" for her.

(Sources: KAW (ed.), quotations are compiled from Erika Buchmann, "Die Frauen von Ravensbrück", p. 126, Kongress-Verlag Berlin, 1959 and Kathrin Mess, "„…als fiele ein Sonnenschein in meine einsame Zelle.../ as if a sunshine fell into my lonely cell". The diary of the Luxembourger Yvonne Useldinger from the women's concentration camp Ravensbrück; p.116, 173, Metropol Verlag, 2008)

Joška Jabůrková (16.04.1896-31.07.1942)

Joška Jabůrková, a Czech woman, gained her first political experience during her engagement for the Czech miners and against the war. She was editor-in-chief of the communist women's magazine "Die Säerin" (The Seedwoman), wrote fairy tales for the workers' children, wrote political writings.

In Ravensbrück she participated in the formation of training circles and in the training of female teachers.

(Source: KAW (ed.), quotations compiled from Erika Buchmann, "Die Frauen von Ravensbrück", p. 128, Kongress-Verlag Berlin, 1959)

Yevgenia Lasarevna Klemm (1898-1947)

Yevgenia Lasarevna Klemm, studied education and was a professor at the University of Odessa, a Red Army prisoner of war, secretly taught other prisoners Russian literature and history during the few hours off work.

Although forbidden and punished with severe punishments, women from other nations / barracks also attended her "lectures". In this way she became known and popular with many women in the camp. She was a living example of the thought and deed of international solidarity.

She was spokeswoman for the illegal anti-fascist group of Soviet women in Ravensbrück.

Lidia Besnogova wrote in her memoirs: "On November 7, 1944, between the end of work and the evening siren, a number of communists, two of each nationality, gathered in the Soviet prisoner of war block, among them Rosa Thälmann and Mela Ernst. The anniversary of the October Revolution was commemorated. Jewgenia Klemm described the situation at the front, which was already running along the Oder, and ... that liberation must come soon. At the end there was a quiet singing: 'Fatherland, no enemy shall endanger you'.

(sources: "Frauen aus Ravensbrück / Women from Ravensbrück ". Calendar 1995, Sigrid Jacobeit, MGR (ed.); KAW (ed.), quotations compiled from Erika Buchmann, "Die Frauen von Ravensbrück", p. 129, Kongress-Verlag Berlin, 1959)

Olga Benario Prestes (1908 - 1942)

Secret teaching and learning was part of the struggle for survival for many women.

Olga Benario Prestes, the Block Elder in Barrack 11 for Jewish women, secretly organised courses and training, drawing miniature maps in pencil.

She was very protective of her companions in suffering and urged them not give up, and by taking part in the courses - forbidden by the camp SS - she strengthened their mental defensive and resistance will.

(“Frauen aus Ravensbrück / Women from Ravensbrück”, Calendar 1995, Foundation Brandenburg Memorials / Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück (ed.), Edition Hentrich 1994, ISBN 3-89468-153-5; see also Ruth Werner, "Olga Benario", Berlin 1961)

Vlasta Kladivová and Vera Hozáková

An outstanding testimony to the unbroken will and vitality of the women in the Ravensbrück concentration camp is the collection of poems and songs secretly prepared by the Czech women Vlasta Kladivová and Vera Hozáková in Ravensbrück in 1943/44 under the title "Europa v boij 1933 - 1944".

Many of the women wrote poems during their imprisonment, many of them could be handed down, because other women secretly organized writing materials from their workplace, because they learned the poems by heart and, if possible (sometimes only after liberation), wrote them down.

The texts were hidden on the body, in the clogs, in cracks in the barracks, at the risk of their lives. They were memorized during roll call or while working, before falling asleep or on the way to work, spoken together, passed on, given to friends on birthdays and name days.

(Source: Constanze Jaiser, Jacob David Pampuch (eds.) „Europa im Kampf 1939-1944 / Europe in Fight 1939-1944: International Poetry from the Women's Concentration Camp Ravensbrück", Metropol Verlag 2005, ISBN 3-936411-61-1)

Grazyna Chrostowska (1921-1942)

Grazyna Chrostowska was able to write poetry even under the conditions of the Concentration Camp.

Comrades wrote them down secretly or learned them by heart. They succeeded in smuggling some of them outside, together with news of executions and pseudo-medical experiments on young Polish women. BBC London informed the world public about this in 1943.

Some poems appeared in illegal or exile magazines.

(“Frauen aus Ravensbrück / Women from Ravensbrück”, Calendar 1995, Foundation Brandenburg Memorials / Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück (ed.), Edition Hentrich 1994, ISBN 3-89468-153-5;)

Józefa Kantor (1896-1990)

Józefa Kantor together with other Girl Scouts, helped numerous refugees from the western regions of Poland in her hometown of Tarnów after Germany's invasion of Poland. She cooperated with Caritas and spread news from the Polish underground press.

In September 1941 she was transported to Ravensbrück after being held in Tarnow prison for about a year.

Here she met two companions from the pre-war period. They began to build up a conspiratorial scout organisation "Mury" (Walls) and recruited further members.

Józefa Kantor conducted Sunday services in the Polish barracks.

(Sabine Arend, Insa Eschebach (ed.), Ravensbrück : “Christliche Frauen im Konzentrationslager / Christian Women in the Concentration Camp 1939-1945”), p. 133, 2018 Metropol - Verlag, ISBN 978-3-86331-382-1)

Margarete Buber-Neumann (1901-1989)

Margarete Buber-Neumann wrote:

"The combination of monotony and constant threat, which determined the atmosphere of the concentration camp, increased the intensity of genuine friendships among the prisoners; after all, they were more exposed to fate than any shipwrecked person could ever be.

The SS decided on life and death, and every day could be the last.

In this situation, forces were roused in us, mental, spiritual and physical forces, which in normal life usually are concealed. In this deadly atmosphere, the feeling of being needed by another person led to the greatest happiness, made life worth living and gave us the strength to survive."

(“Frauen aus Ravensbrück / Women from Ravensbrück”, Calendar 1995, Foundation Brandenburg Memorials / Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück (ed.), Edition Hentrich 1994, ISBN 3-89468-153-5; quotation from the book " Milena - Kafka's Friend” by Margarethe Buber-Neumann)

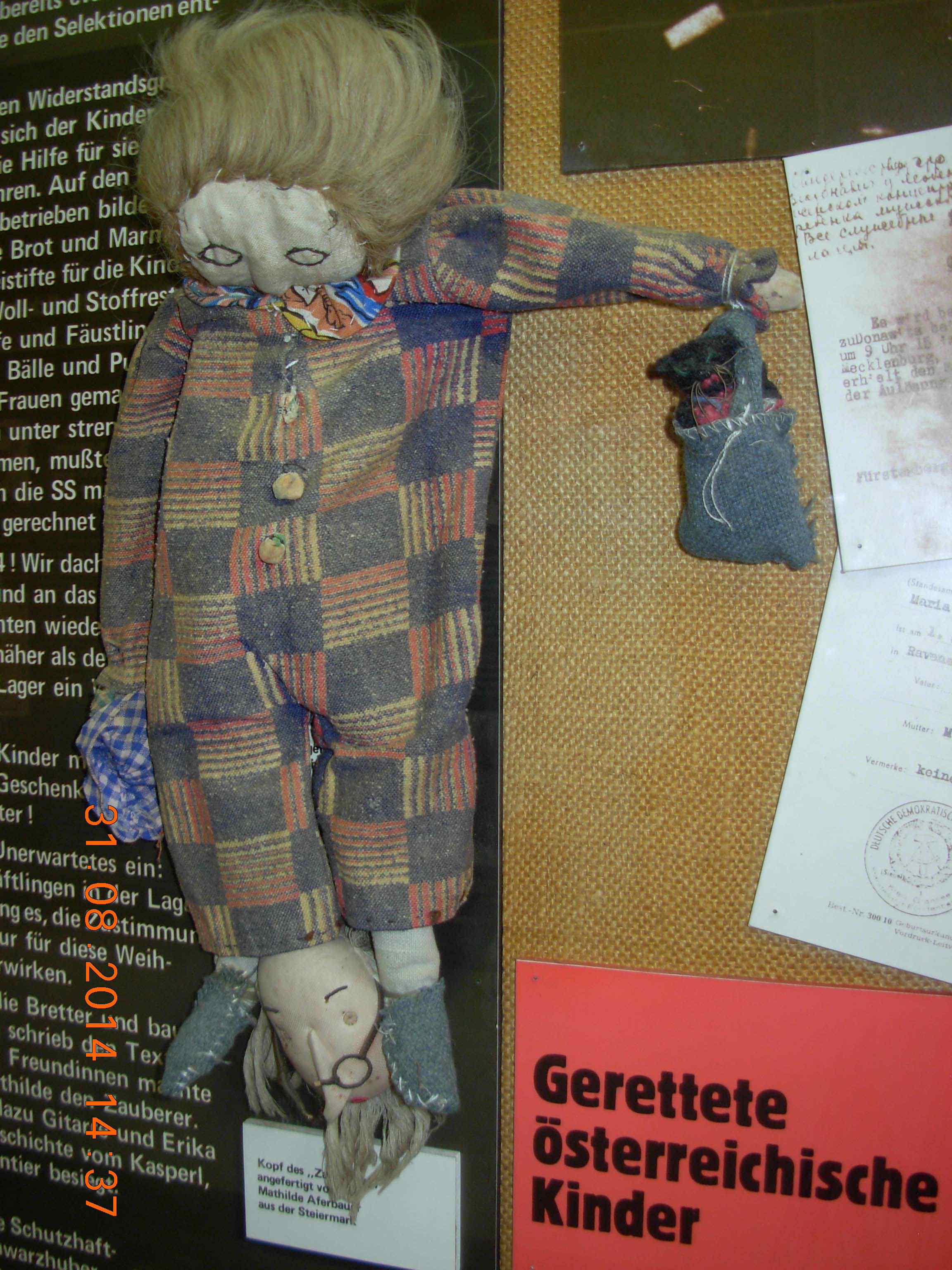

Christmas 1944

The children's Christmas celebrations were one of the most important and largest solidarity actions in the camp. Many women from different nations were involved in its preparation and implementation. It gave the women new courage to face life, made them become active for a good cause and brought joy to many of the children imprisoned in Ravensbrück Concentration Camp in the winter of 1944.

Berta Lauscher (Austria) reported:

It all started with the decision of the international Ravensbrück Committee, which was working secretly in the camp and which was made up of resistance fighters from various European nations. In autumn 1944 it was unanimously decided to set up an illegal Children's Commission, whose task was to form groups together with all prisoners ... which would not only care for bread for the children, but also for their mental and spiritual condition.

On every prisoner block, in every camp operation, groups were formed which began to collect bread and jam and - as far as possible - other food. They also collected sewing needles, scraps of wool, scraps of cloth, paper, pencils and clothes from various camp enterprises. Stockings and mittens were knitted, shirts sewn, caps made, balls and dolls made from old rags. This work had to be carried out under the most stringent of precautions and the most difficult of conditions, because if discovered, punishment block, bunker, beatings with sticks and worse were certain. …

So we had the idea of giving the children a Christmas in 1944 to give them a little love, warmth and 'faith in the good in people', as Anne Frank said in her diary.

Now we faced something unexpected: Via the camp secretary's office we were able to get permission to hold the Christmas party. It was probably due to the fact that there was already a great deal of uncertainty under the SS because of the catastrophic course of the war under Hitler's Germany.

Full of enthusiasm and with the ardent desire to see the children laugh once and fill their empty stomachs a little, the women of Ravensbrück developed a passionate activity.

The proposal was made to perform a Punch and Judy show. And there the women of different nations and professions showed their skills. …

(Source: „Frauen-KZ Ravensbrück… und dennoch blühten die Blumen. Dokumente, Berichte und Zeichnungen vom Lageralltag 1939-1945"; p. 110/111, Bertl Lauscher, DÖW:Kz-Ra, ed.: Helga Schwarz, Gerda Szepansky, Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2000, ISBN 3-932502-25-6)

Vera Hozáková (Czechoslovakia) remembers:

"With Kveta, a painter, I sit at work in the evening, and under our hands we make other dolls - a princess, a prince, a Kaspar, a devil, robbers, a dragon... We pull them over our hands and they're alive. ... The girls in the workshops are building the showcase, Tonicka from Vienna (meaning Toni Bruha) is writing a fairytale.

We play in the unfinished children's block, in a huge, empty, unfriendly room. Felicie plays the guitar, and Erika tells the fairy tale of Kaspar and the robbers with her beautiful voice. I sit in the box with Kveta, and the dolls on our hands move to Erika's words. The game ends with guitar chords. It is silent.

Through a crack in the curtain we look at the shining eyes. They are still completely in the other world, in a world unknown to them, but which also means joy and beauty for them - the victory of good over evil.

(Source: Vera Hozáková: Und es war doch... / I to prece bylo ... Ravensbrück Memorial, 1995, p.40-41)

*Poldi Morawitz *(Austria) remembers:

My desk was located in the camp's headquarters, the so-called Kommandantur, in a small room just beneath the roof. There I had to label record cards. In December 1944 I sometimes kept some craft materials in my lap and created presents for the children when the situation would allow for it. On one particular day I worked with some grey waxed paper which then transformed into a small elephant as a present for one of the children. I had cut out the shapes of the elephant and was in the midst of sewing them together. Later the space in between would be filled with some other soft material. Suddenly an SS officer was standing behind me, Herr Bunte! I was terrified and expected the worst. But he did not yell at me and asked me instead if I could make another such elephant for him, soon being Christmas and all...

I just nodded – I had no other choice, of course. He really did not deserve it! Later that evening I told the others about it. I felt bad that I had been discovered. Now, our preparations were not secret anymore. The other women suggested I do Bunte the favour so as not to endanger the whole Christmas party. So Bunte got his elephant.

(written down by Poldi Morawitz' daughter, Dr. Brigitta Kauers)

There were several Christmas celebrations in December 1944. Marta Baranowska (Poland, block elder):

"There were eighty-six Polish children of all ages on the block. ... The field workers got me eighty-six bags with some Christmas stuff on them. And I tried. I put the eighty-six bags in the duty room and I tell the girls: "Kids, we're gonna have a party for the kids, and I want those bags filled. But from the East there were already very few parcels sent to us. But parcels were sent to the women who were in the officers' camp. Such beautiful parcels came from Switzerland ... And from these rare parcels, ... I filled the eighty-six bags. They were standing in the duty room in Block 1.

Once the Binz came in and said: Yeah, what is this?! Well, we want to make the party for the kids. I collect the bags, so that the children at least have joy on Christmas Eve. There are more children. Well, how can I do for hundreds? I say: Warden, please allow me. This is a very special holiday for us, Christmas Eve. Allow me to make this happen for the children. And I promise you, we'll make a Christmas for the gypsy children. She's agreed to it...

The artist appeared, a beautiful woman with long black hair down to her knees, Anna Lubrina, Sascha Wisch, an actress, ... And the children were presented with these bags, which became full during several weeks. It was the most touching. Sometimes they would bring me just a handful of sugar or a tin, something nice, or a cookie and so on. And that was a joy!

(From an interview of Loretta Walz with Marta Baranowa 1997 in Bydgoszcz)

What happened to the kids?

The women couldn't protect them. "One day ... in early 1945 my comrade Relly Eisner came running to me and shouted: "Sternderl, your children are leaving!" We ran, ignoring all the dangers, across the roll call area to the camp gate. It was too late. The SS had occupied the camp square in front of the camp gate. We had to watch as the children were led out of the camp together with old women - to their death! Even today I could scream when I think about this." (Bertl Lauscher, Doew:Kz-Ra)

For many children it was the only and last Christmas party in their short lives.

At the beginning of 1945 several transports left Ravensbrück for Bergen-Belsen. The conditions there were even more devastating than in Ravensbrück.

When the Ravensbrück camp was evacuated at the end of April 1945 and the women prisoners' were driven on the death march, there were only a few children still alive